The arrest of former soldier Steven Green, and in particular the public filing of the FBI affidavit in federal court Monday to support the charge of murder and rape against him, makes it somewhat pointless to post the timeline I pieced together over the weekend. The

Washington Post account is the best of those available. The Post's previous

reporting on the neighborhood and family of the victims is also indispensable.

I didn't have the stomach to post about the case on the Fourth of July, much less to approach it from the angle that

Billmon has. But now that many more facts in the case are out in the open, I'll take the opportunity to review the information that supports (and that undercuts) a connection between the Mahmoudiyah crimes and the kidnaping/murder/mutilation of Kristian Menchaca and Thomas Tucker. I'll also offer some further thoughts and questions.

First, and fundamentally, the Mahmoudiyah accused were part of the same platoon as Menchaca and Tucker: 1st Platoon, B Company of the 1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry regiment. A platoon contains only 40 men or so. The 502nd is part of the 101st Airborne Division, based at Ft. Campbell, Kentucky, but has been attached to the 4th Infantry Division during this deployment. Since at least late November 2005, B Company has operated in the 'Triangle of Death' area south and southwest of Baghdad.

Second, at least two non-participating members of the platoon had an idea of what had happened. Despite the participants' warning among themselves not to say anything about the events of that night ever again, it seems clear that some of them did. Sometime in April, Private Green, the apparent ringleader of the March crimes, was

sent back to Ft. Campbell. On May 13, he was discharged for an unspecified "personality disorder." To those in the unit who knew or had heard rumors about the atrocity in Mahmoudiyah, Green's departure had to have been a reminder -- no matter how unrelated the events leading to his discharge. (To those who participated in the crime, Green himself was a daily reminder, so that his departure might well have been a relief: out of sight, out of mind.)

Third, some locals became aware that Abeer Hamza had been violated, although the immediate neighbors and relatives of the murdered family appeared to believe initially that the attackers were Shiite militia. The rape and killings took place only a few weeks after the destruction of the golden mosque in Samarra, which set off an intensified wave of sectarian attacks and prompted many families to move from mixed neighborhoods into solidly Shiite or Sunni ones; the Hamza family had only recently moved to the neighborhood. Mahmoudiyah is on the way from Baghdad to the cities of the south, and many Shiites have been killed there and in the area.

But the possibility of danger from the nearby U.S. troops was also known to the family and neighbors. Abeer was a pretty young woman of 15; her complaints about the repeated advances from the soldiers at the checkpoint, only 650 feet from the house, had led her mother to ask a neighbor the day before her death to let Abeer sleep at their house. The neighbor saw the aftermath of the crime, with Abeer's dress pulled up to her neck. Medical officials who handled the body knew she had been raped. The family did not have a public funeral.

Mahmoudiyah hospital officials say that a day or two after the killings soldiers came around to ask where the funeral was. If that's true, both the absence of a public funeral and the soldiers' visits are bound to have raised suspicions outside the family. There is also this, from the CBS/AP

story of July 1:

Mahmoudiya police Capt. Ihsan Abdul-Rahman said Iraqi officials received a report March 13 alleging that American soldiers had killed the family.

There is a history of civilians killed by U.S. troops in the area; another police officer

mentioned "a shooting at a checkpoint in April that left 11 Iraqis dead." However, I should note that statements from the Mahmoudiyah police have proven the least reliable of any of the original reporting on this story. Different officers, on the record, have given detailed, specific accounts to reporters, but the accounts are wildly incompatible with each other.

Fourth, the Mahmoudiyah perpetrators and Menchaca and Tucker were serving in very similar situations at the time of the events that made them notorious: manning a checkpoint in a small group, relatively isolated from their base and from other units. Three months after the Mahmoudiyah crime, when Spc. David Babineau was killed and the other two taken away in an attack on their checkpoint at Youssufiyah, the possibility that it was a revenge attack might have occurred to those who knew about it. On the other hand, attacks on U.S. forces are so common in the area that no connection may have been made at the time.

Fifth, kidnaping of U.S. soldiers has been extremely rare during this occupation. The scale and publicity of the hunt for Menchaca and Tucker was unlike anything B Company members had experienced in their time in Iraq. The discovery of the mutilated bodies in Youssufiyah on June 19 was wrenching enough, but the agony was prolonged by the length of time it took to disarm the many bombs laid along the path to the bodies, a process that killed another soldier and wounded several more.

Sixth, the disclosure of the crimes came about only days later, when soldiers in the 1st platoon were being counseled in the aftermath of the recovery of Menchaca's and Tucker's remains. The first to talk were two men who had not taken part but had heard about it. Whether or not the kidnaping/killings had been a revenge attack, the soldiers who revealed the Mahmoudiyah crimes made a connection between them. The Army criminal investigation began the next day. One of the participants still in Iraq admitted to his part; some stories said that he has been charged, but the

Post reporting contradicts that, and there is no confirmation from the Army so far.

Questions small and large occur. On the small side: How did the men in Green's "fireteam" get access to alcohol, much less feel free to drink it while on duty? Where did they get the

shotgun and rifles they carried to the Hamza house? Are active-duty soldiers allowed to keep non-military-issue weapons? Where is the base for B Company, and how far is it from Youssufiyah and Mahmoudiyah? Had Ryan Lenz, an AP correspondent embedded with the 520th until early June and the first to

report the story, heard of the Mahmoudiyah crimes before the Army announcement on June 30?

But the main question that this horrifying crime raises is the same one that has been with me since March 2002, when I realized that this invasion and occupation was going to happen:

What the hell business do U.S. troops have being in Iraq?Bring 'em home.Update: 2:00 pm, 6 July - Thanks to elendil in comments, who pointed to this LA Times

story, which says the military is investigating whether the two incidents are connected. My prediction is that they'll find the official answer to be 'no'.

Labels: Iraq mil

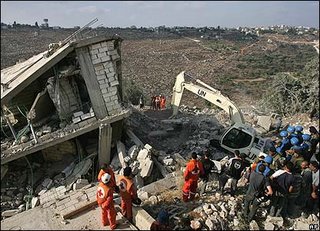

Taken Sunday morning July 30, the picture shows the house where Israeli air strikes killed sixty people, including somewhere between 27 and 37 children. The BBC reporter on scene described it as having been "crushed sideways into an enormous crater" by the strike, which took place in the dead of night (midnight or one o'clock).

Taken Sunday morning July 30, the picture shows the house where Israeli air strikes killed sixty people, including somewhere between 27 and 37 children. The BBC reporter on scene described it as having been "crushed sideways into an enormous crater" by the strike, which took place in the dead of night (midnight or one o'clock).